What I've learnt from Advent of Code 21

Approx: 10 minutes reading timeAs I only made it to day 8 last year, I was even more determined to finish this year’s Advent of Code. I have to admit it’s been hard to find the time on occasion, but it’s been one of my top priorities for the month of December and I’ve managed to complete each task with the day, every day. If you follow me on Twitter, I apologise for the sheer amount I posted about this over the course of the last month 🤣

Advent of Code 2021

Advent of Code is an Advent calendar of small programming puzzles for a variety of skill sets and skill levels that can be solved in any programming language you like. People use them as a speed contest, interview prep, company training, university coursework, practice problems, or to challenge each other.

Of course, I’ll talk about my solutions, but I’ve also included some other great solutions, written in Swift, that I’ve learnt from, and I’ll reference as I go through:

GitHub - Oliver-Binns/Advent-of-Code: My solutions for Advent of Code

My solutions for Advent of Code

Readability

When working under time pressure, aiming for readable code is often one of things we stop doing. In general, Swift can be quite a readable language; I’ve seen a lot of illegible code (usually in Python) flying around this year. Usually this is a result of variables being given generic, rather than meaningful names, like x, y, perms or index.

Daniel Tull‘s solutions are a great example at prioritising readability even when under pressure, he’s done a fantastic job at abstracting code out of each day’s solution into helper files, and then separating the files themselves using extensions. All the variables are well named and it’s always easy to tell what each line of code is doing.

Advent-of-Code/Day10.swift at main · danielctull/Advent-of-Code

My solutions to the Advent of Code puzzles. Contribute to danielctull/Advent-of-Code development by creating an account on GitHub.

Consider his Day 7 solution. On Day 7, we needed to find the cheapest solution for moving a set of crabs into a horizontal alignment from their given staring positions. Both part 1 and part 2 of Daniel’s solution reuse the same general solution and the rest reads almost like spoken English. We receive an input, get the first line and separate it at each comma and transform each value to integer.

let positions = try input.lines

.first.unwrapped

.split(separator: ",")

.map(Int.init)

Then we find the minimum and maximum values. For each value between the minimum and maximum, we test the total costs of moving the crabs and return the minimum value.

let min = try positions.min().unwrapped

let max = try positions.max().unwrapped

let amounts = positions.countByElement

return try (min...max).map { proposed -> Int in

amounts.map { position, amount in

cost(proposed, position) * amount

}

.sum

}

.min()

.unwrapped

When writing readable code, another important factor is trying to reduce distractions and clutter. As well as brevity, this can include not reinventing the wheel. Regarding this, I was very impressed by Sima Nerush‘s Day 1 implementation. She’s used Swift’s new Algorithm’s package to produce one of the most minimal implementations I’ve seen. Completing both challenges in just 23 lines is incredible, in contrast my implementation was more than double this!

import Algorithms

import Foundation

final class Day1: Day {

func part1(_ input: String) -> CustomStringConvertible {

return input

.split(separator: "\n")

.compactMap { Int($0) }

.adjacentPairs()

.count { $0 < $1 }

}

func part2(_ input: String) -> CustomStringConvertible {

return input

.split(separator: "\n")

.compactMap { Int($0) }

.windows(ofCount: 3)

.adjacentPairs()

.count {

$0.sum < $1.sum

}

}

}

advent-of-code/Day1.swift at main · simanerush/advent-of-code

solutions for advent of code with swift! Contribute to simanerush/advent-of-code development by creating an account on GitHub.

Complexity

Since there are two (related) challenges to complete each day, often the first is easier than the second. On several occasions the difference is simply down to a requirement for additional computation. A solution that may quickly return an answer for the first task, may take hours or days to run for the extension task.

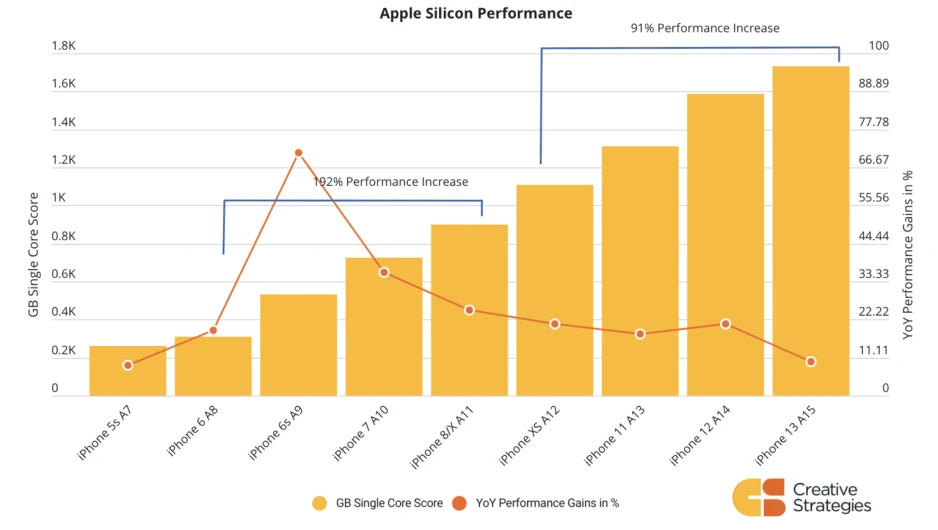

For me, this has been one of the hardest parts of Advent of Code. It's been a few years since I was at university studying the theory of computational complexity and I've definitely gotten a little rusty. As most mobile devices now have an unbelievable amount of computing power (see the graph below!), I don't often need to produce code that is highly efficient in my day to day work. However, by knowing these techniques, we can write better code and reduce the impact of our inefficient code on the device's battery life.

Apple Silicon Single Core CPU Performance from iPhone 5s to iPhone 13 (c) Creative Strategies

By reading other’s solutions, I’ve found some handy tricks that I’ve managed to incorporate into some of my own code. In particular, I struggled with the extension puzzle of Day 6 and had to take some inspiration. For the first half, I implemented the solution modelling every single fish:

func solve(filename: String) throws {

let fish = try openFile(filename: filename)

.filter { !$0.isWhitespace }

.components(separatedBy: ",")

.compactMap(Int.init)

return (0..<80).reduce(fish) { fish, _ in

fish.flatMap(nextDay)

}.count

}

func nextDay(fish: Int) -> [Int] {

guard fish > 0 else {

return [6, 8]

}

return [fish - 1]

}

Unfortunately, as the fish population grows exponentially, this method becomes untenable once we run for longer than about 100 days. The code takes a very long time to run and will likely even cause the computer to run out of memory! I needed to do better.

I loved this implementation from Abizer, where instead of tracking each fish, he tracks the number of fish that are on each of the 8 days of the reproductive cycle. I especially liked the use of Dictionary(_ keysAndValues: S, uniquingKeysWith combine: (Value, Value) throws -> Value) for summing up the fish for each day. So, for example, this initialiser, combined with the map turns [0, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 4, 5] into [0: 1, 1: 1, 2: 2, 3: 2, 4: 1, 5: 1].

public static func part1(_ input: String) -> String {

let inputDictionary = generateDictionary(input)

return "\(countPopulation(of: inputDictionary, over: 80))"

}

static func generateDictionary(_ input: String) -> [Int: Int] {

Dictionary(input.intsFromLine.map { ($0, 1) },

uniquingKeysWith: +)

}

static func countPopulation(of input: [Int: Int], over: Int) -> Int {

(0 ..< over).reduce(into: input) { start, _ in

var end = [Int: Int]()

start.forEach { key, value in

if key == 0 {

end[6, default: 0] += value

end[8] = value

} else {

end[key - 1, default: 0] += value

}

}

start = end

}

.values

.reduce(0, +)

}

I hadn’t come across this dictionary initialiser before, but it really came in handy and I used it on days 6, 7, 8 and 14.

AdventOfCode/Solution9.swift at main · Abizern/AdventOfCode

Advent of Code solutions in Swift. Contribute to Abizern/AdventOfCode development by creating an account on GitHub.

Immutability

At university one of the most difficult modules I took was on Functional Programming in Haskell. At the time I couldn’t quite get my head around the concept of immutability in programming. I struggled to grasp how to handle changes in state when using value types. It’s definitely true that immutability becomes harder to use when state is involved; by definition state can change. Generally the solution is to change the whole state at the same time.

For most of these challenges, since the state can be fairly lightweight while the computation is heavy, immutability can be a great choice. In general, immutable objects provide a number of benefits. In our world of increasing parallelism (iPhone 13 has 6 CPU cores, 16 NE cores and 4 GPU cores), immutable objects can safely be passed between threads without risking synchronisation issues. We can also implement better encapsulation, passing our objects into other functions secure in the knowledge that they won’t be modified. This has the additional benefit of making our code easier to test as we don’t have any side-effects to analyse.

Consider my solution to Day 6, above. Each day we return a completely new array representing the new state of the fish population. When state is simply represented by an array of integers like this, it’s simple enough. For more complex types of state, such as Day 4’s sets of bingo boards, I regressed to my old habits of mutability, with the boards being edited rather than a new state being created. I’ve seen a number of solutions similar to mine, which avoid mutability for everything part from marking the number of each board after it’s called. However if you’ve managed an implementation with complete immutability, I’d be interested to see it.

Test-Driven Development

At the start of the month I set up my project as a bunch of standalone script files. One of the things I’ve longed for, particularly with the later challenges is the ability to write some unit tests for some of my code. This would really help me to ensure that my code is outputting the correct results against the examples that are given.

On Day 18, in particular, I went down a rabbit hole from having not read the question properly. Here, where we had to split a single regular number that is 10 or greater, I was splitting every regular number that was 10 or greater. By writing a unit test of input vs expected output, I would have saved myself a lot of time!

If any regular number is 10 or greater, the leftmost such regular number splits.

— Day 18, Advent of Code, 2021

This is exactly what Dave DeLong has done, using a Swift Package to allow testing. This seems like a great way to set up the project and I’ll definitely be following his lead next year. A Swift Package, much like the Swift Playgrounds that others have used, also makes it far easier to share code between challenges, in stark contrast to my scripting where I’ve needed to copy and paste small snippets into each individual solution.

GitHub - davedelong/AOC: Advent of Code

Advent of Code. Contribute to davedelong/AOC development by creating an account on GitHub.

Remote Builds

A random one, but I thought Leif Gehrmann‘s use of GitHub actions to run his code was great. It takes your current hardware out of the picture and lets you independently prove how quickly your solutions run for comparison against others.

GitHub - leifgehrmann/advent-of-code: Advent of Code

Solutions to Advent of Code 2021 in Swift. Day-19 - Parts 1 & 2 of the puzzle solved! But I did everything manually, so this is not a generic solution. · leifgehrmann/advent-of-code-2021@b31fd34

Thanks for Reading

Thanks to Eric Wastl and all the sponsors for making Advent of Code 21 happen. The puzzles have been super interesting; I’ve definitely felt challenged, but I’ve relished it and seeing the innovative ideas and solutions that others have had has made it even more compelling to be a part of. I’ll be seeing how I can start to use the things I’ve learnt in day to day work, and I’m already looking forward to next year’s challenge!