Going iOS native with WordPress

Approx: 9 minutes reading timeWordPress is one of the most popular website platforms available, in fact it powers just under a third of the entire web, including this very website. WordPress is a great tool for all kinds of websites, and the web in general is great for distributing content to a massive number of users, but it cannot match the user experience that can be provided through native apps.

As most of my work focusses on iOS, I decided to use the WordPress API to see if I could make my blog (this website) available as a native app. I released this recently – you may even be using it to read this post – though I’ll let you be the judge of how well it’s been executed.

Oliver Binns on the App Store

Read Oliver Binns’ Blog in the app optimised for iOS devices. The app supports dynamic type, VoiceOver and can be used without installing thanks to App Clips on iOS 14.

Why?

Web

Supporting Web allows the site to be accessed by the widest possible number of users. The website is available to users on Desktop PCs, smartphones from all manufacturers*, tablets and even TVs.

*Disclaimer: I haven’t checked them all.

Native

Native apps feel more intuitive to users as they tend to follow the UI standards of the individual operating system more closely. While this app is relatively simple, making it native would allow it to make the most of the vast array of APIs and hardware available on iOS devices.

For starters, this app makes the most of the accessibility features in iOS by providing support for Dynamic Type and VoiceOver, as well as giving users the ability to read posts while they are offline. You can see from these images that the iOS app obeys the user’s dynamic type choice while the web app displays text at the default size.

Blog post viewed on the web in Safari Blog post viewed on the web in Safari |  Blog post viewed in the native iOS app Blog post viewed in the native iOS app |

While it is possible to support dynamic type on the web, we don’t get as much control over it, nor as much given for free as we do using the iOS SDK.

Going native also would allow us to make the most of additional iOS features such as widgets, augmented reality, Pencil, iMessage apps, and so much more.

How?

Backend

Since I use WordPress for writing my blog, there is no need for any extra work to create a backend API for the app. WordPress provides a REST API which I can use to easily query the site to retrieve the list and content of my posts to display to the user. Easy, right?

Making a GET request to https://wordpress-site.com/wp-json/wp/v2/posts:

[

{

"id": 132,

"date": "2020-09-05T16:00:41",

"modified": "2020-10-15T07:50:39",

"slug": "going-for-gold-taking-full-advantage-of-apple-platforms",

"link": "https://www.oliverbinns.co.uk/2020/09/05/going-for-gold-taking-full-advantage-of-apple-platforms/",

"title": {

"rendered": "Going for Gold- Taking full advantage of Apple Platforms"

},

"content": {

"rendered": "

<p class=\"has-drop-cap\">

In a recently published <a href=\"https://www.oliverbinns.co.uk/2020/06/27/create-a-tube-status-home-screen-widget-for-ios-14/\">

blog-post on building widgets for iOS 14

</a>

..."

}

}

]

We can represent this as a UML diagram, to give visual representation of the different objects we can create in Swift and how they are related.

UML Class Diagram for WordPress post API

If you’ve read some of my previous posts, you’ll be familiar with Swift’s Decodable protocol for decoding values from JSON representation.

Although we can convert this directly into a Swift struct representation...

struct Post: Decodable {

let id: String

let slug: String

let title: String

let link: URL

let jetpack_featured_media_url: URL?

let date_gmt: Date

}

For Swift beginners: a struct is similar to a class, but more lightweight and recommended as the default building block for Swift objects. For a full comparison of the two, I’d recommend reading this chapter from the Swift Language Guide.

... it would be much better to use CodingKeys to transform these variables to more closely follow the Swift Naming Guidelines, including the use of camel-case rather than snake-case:

struct Post: Decodable {

let id: String

let slug: String

let title: String

let link: URL

let imageURL: URL?

let publishedDate: Date

enum CodingKeys: String, CodingKeys {

case id, slug, title, link,

case publishedDate = "date_gmt"

case imageURL = "jetpack_featured_media_url"

}

}

Not so fast...

While this means we can easily get the lists of posts using a simple API query in our iOS app, we still need to convert that rendered content into native iOS components. I defined a set of components that I use to write the blog and created an enum in Swift:

enum PostContent {

case heading1(String)

case heading2(String)

case body(NSAttributedString)

case image(URL)

case horizontalRule

...

}

I used SwiftSoup to parse the HTML string provided by WordPress:

let xml = try? SwiftSoup.parse(contentHTML)

We can create an initialiser for converting SwiftSoup‘s Element type into our enum...

extension PostContent {

init(element: Element) throws {

switch element.tagName() {

case "h1":

self = try .heading1(element.text())

case "hr":

self = .horizontalRule

// etc.

// ...

}

}

}

...then map our rendered content into the PostContent type we just created:

let content = xml?.body()?.children().compactMap {

try? PostContent(element: $0)

}

ViewBuilder

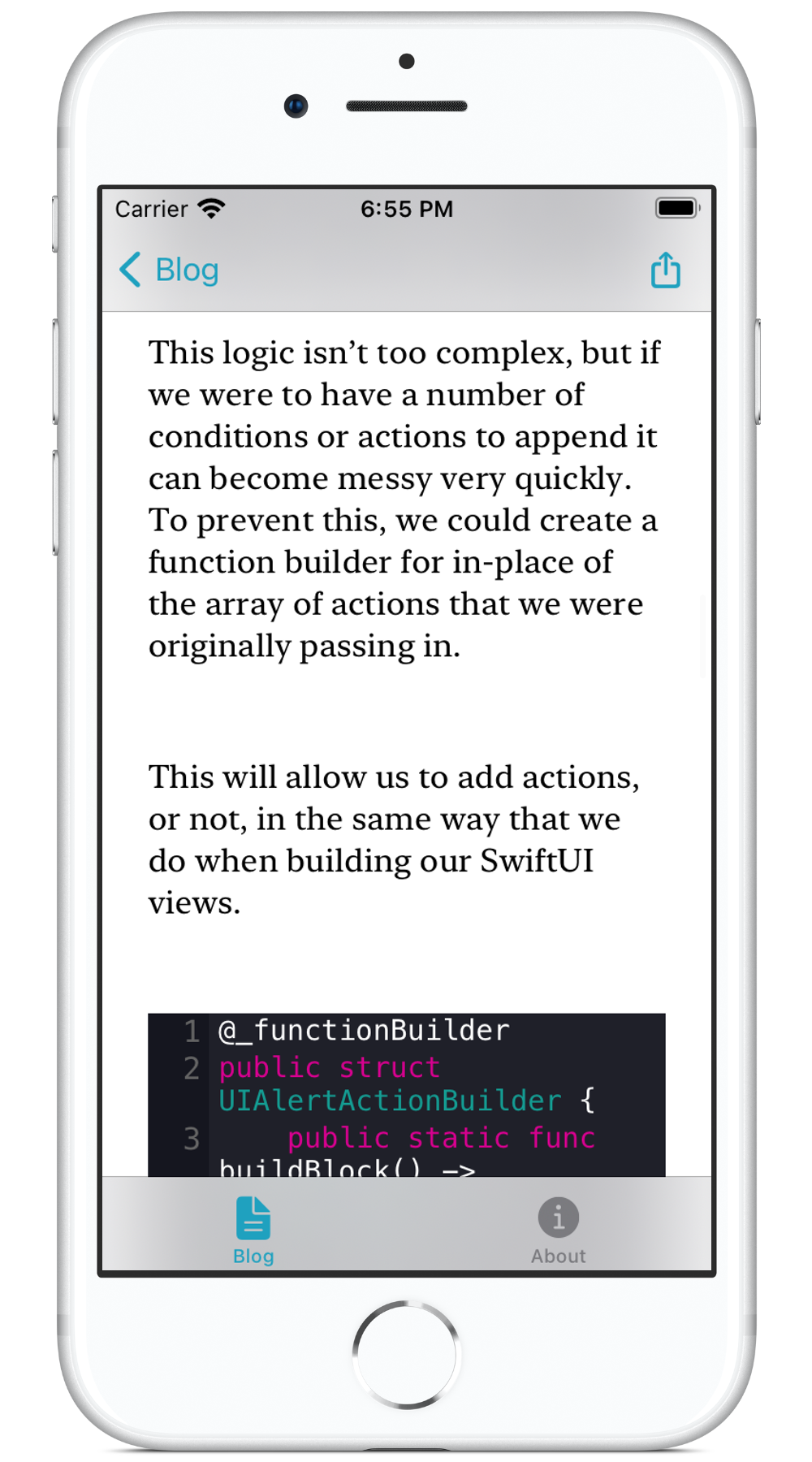

Now that we’ve converted the raw HTML string into a data model, we can think about transforming this into views that we can display on the screen. I’ve used SwiftUI for this, but we could add specific implementations for UIKit or AppKit, or even something a bit more off-piste such as exporting to PDF or another type of document.

SwiftUI’s ViewBuilder allows us to easily map our internal PostContent type into its SwiftUI representation, using a set of very readable code.

@ViewBuilder

func viewForContent(_ content: PostContent) -> some View {

switch content {

case .heading1(let string):

Text(string).font(.title)

case .heading2(let string):

Text(string).font(.title2)

case .horizontalRule:

Divider()

// etc.

// ...

}

}

Using SwiftUI, we get support for many of the great native features I described above, including dynamic type, dark mode and more, out-of-the-box. This works great for the majority of the components. As you can see from the code-snippet above, some elements, such as the horizontal rule, can be mapped directly. However some may require a little bit more work.

Paragraphs

Overview

Supporting rich-text with bold text, links and more isn’t easy in SwiftUI as it has no out-of-the-box support for rendering HTML or NSAttributedString. I found the easiest way to implement is to bridge into UIKit with a UIViewRepresentable class to display a UILabel which will display the HTML content provided by the API using NSAttributedString. If all this sounds like Greek to you, don’t worry: I will explain it step-by-step!

Decoding

Our response from the server will return content which should be displayed like this:

“This is a paragraph containing some bold, italic text.”

However, since the server returns raw HTML text, if we decode this directly into a Swift string, we will display:

“This is a paragraph containing some <b>bold, <i>italic</i></b> text.”

Luckily the iOS SDK provides an easy way to turn this into an NSAttributedString which can be displayed on the screen with the bold and italic characters we would expect.

let excerpt = try? NSMutableAttributedString(

data: Data(excerpt.utf8),

options: [.documentType: NSAttributedString.DocumentType.html],

documentAttributes: nil)

You can find more details in this article from Paul Hudson:

Hacking with Swift

How to convert HTML to an NSAttributedString

Rendering

Unfortunately SwiftUI doesn’t support rendering of NSAttributedString out-of-the-box, but with a bit of work, we can create a new AttributedText struct which will!

To do this, I’ve chosen to use UITextView, rather than UILabel, as it has inbuilt support for HTML links- but don’t forget to disable editing!

struct SwiftUILabel: UIViewRepresentable {

// We can pass in the text we initialised above!

@State var attributedString: NSAttributedString?

func makeUIView(context: UIViewRepresentableContext<Self> -> UITextView {

UITextView()

}

func updateUIView(_ uiView: UITextView,

context: UIViewRepresentableContext<Self>) {

uiView.isEditable = false

guard let attributedString = attributedString else {

return

}

uiView.attributedText = attributedString

}

}

Great, now let's run it:

HTML mark-up rendered as a UILabel within SwiftUI.

It works! Our text appears bold, italic, underlined and even in a monospaced font as we would expect. We even get support for numbered and un-numbered bulletpoints.

There’s just a small problem, and it’s hard to spot, but SwiftUI doesn’t seem to obey the intrinsic content size of the UILabel, so we get some large gaps in between our content.

Here’s the comparison:

SwiftUI adds too much padding above and below the text. This causes some layout issues in the scroll view. SwiftUI adds too much padding above and below the text. This causes some layout issues in the scroll view. |  |

I’ve found that the best way to do this is to place the SwiftUILabel inside a wrapper which can manually set the frame to the height. We can use a binding to pass the expected height through to the inner type: this allows both to stay up-to-date with the latest value, with any changes being rendered on the screen.

import SwiftUI

import UIKit

struct AttributedText: View {

// We can pass in the text we initialised above!

@State var attributedText: NSAttributedString?

@State private var desiredHeight: CGFloat = 0

var body: some View {

HTMLText(attributedString: $attributedText,

desiredHeight: $desiredHeight)

.frame(height: desiredHeight)

}

}

struct SwiftUILabel: UIViewRepresentable {

// We can pass in the text we initialised above!

// N.B. This has been changed to a binding now!

@Binding var attributedString: NSAttributedString?

// A binding references the state of the parent class

// Any updates we make here, trigger an update on the screen

@Binding var desiredHeight: CGFloat

func makeUIView(context: UIViewRepresentableContext<Self> -> UITextView {

UITextView()

}

func updateUIView(_ uiView: UITextView,

context: UIViewRepresentableContext<Self>) {

guard let attributedString = attributedString else {

return

}

uiView.attributedText = attributedString

DispatchQueue.main.async {

let size = uiView.intrinsicContentSize

guard size.height != self.desiredHeight else {

return

}

self.desiredHeight = size.height

}

}

}

If you know a better way of doing this in SwiftUI, please do let me know!

In the final code, I’ve also added support for links within text which is fairly easy to do thanks to UITextView.

It works!

We’ve used the WordPress API to natively render a website on iOS with support for Dynamic Type and Dark Mode.

The entire source code for this app is available on GitHub:

Oliver-Binns - GitHub

Here's the code that makes up my iOS app, available on the App Store.

Look out for a future article where I’ll describe how I made this app available without users needing to download it using App Clips for iOS 14.